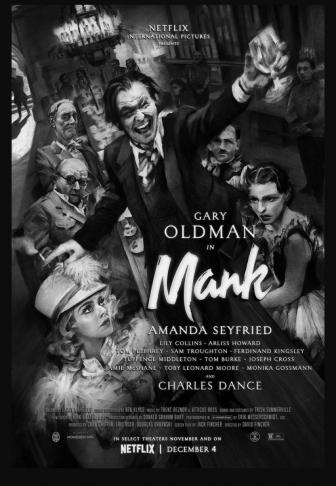

A six-year absence following Gone Girl - an eternity. Six years during which David Fincher made multiple series but practically ceased being a filmmaker. Still for Netflix, and hence out of French theatres, Mank nevertheless marks his return to features. The opportunity to reflect on his umbilical link to cinema and on the eternal relationship between what’s written and what’s filmed. A wide-ranging interview with a giant.

He is the man for the job. You’ve got a million dollar script signed by an unknown, a high-concept in need of a super technician, 200 pages from a star scriptwriter to fit exactly into two hours, a Scandinavian bestseller or an easy-reading feminist novel to transform into a blockbuster thriller, an impossible-to-meet technological or dramaturgical challenge, in any of these cases (which fall in with just about all of his films), you’d call up David Fincher and he’d take good care of it. He’s a film-challenge trouble-shooter, the Swiss Army Knife of Hollywood, the emergency plumber, the 24-hour hotline, the panacea for all your problems. He’s a major director but also, and above all, today’s American cinema’s biggest professional. But no, not today’s but yesterday’s, and, yes, even before that.

Fincher had disappeared from the (big) screen after Gone Girl in 2014. After launching House of Cards, the series which put Netflix on the essential-broadcaster map, we found him as the showrunner and director of half a dozen episodes of Mindhunter then as executive producer for the animated sci-fi series Love, Death & Robots, honouring the Metal Hurlant legacy. His friend Steven Soderbergh explained it in the columns of this magazine two years ago. “David has never worked so hard. Before, it's true, he used to take long breaks between his projects, but now he's working extra hard. On Mindhunter, he is at 2000% at all levels of production, in total immersion.” In total immersion, yes, but on series island, far from cinema shores. A voluntary exile, revealing a malaise, unhappiness, with a studio-system in full mutation.

Mank cannot, must not, be separated from this particular context. In taking as a subject the creation of Citizen Kane, long held to be "the film of films", focusing on a script signed-off by his father, former journalist and film buff, and revisiting the "old Hollywood" in such a meticulous and fetish-like manner as that which Tarantino had reconstituted for 1969 or Cuarón had for the districts of Mexico where he grew up, Fincher has put himself in danger, daring the risk of a major psychoanalytical gesture - a second layer of background images in Mank where he confronts his own ambitions as an artist, the way he practises his trade, his memories of childhood, his passion, his peers and his movie fathers. His father, in short. There are no longer any “super-craftsmen” who hold out through time. No more taking-a-step-back – or overview - posture applied to a script by Aaron Sorkin (The Social Network), Eric Roth (Benjamin Button) or Steven Zaillian (The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo).

Mank is a personal affair, a family affair, an "exorcism" (he himself uses the term) and a deep-water dive into his creator-brain, where everything telescopes together - his relationship to images, his own, those of others, the true ones, the false ones, his relationship to the words, those of his father, those of his writers, those written in the 1930’s and 1940’s and no-one would write anymore, because no-one would be able to.

Like many Netflix movies - this is their strength – Mank shouldn’t exist. Black and white, intimate up to a form of autism, theoretical, experimental, squarely meta, or “cubely”, Fincher attempts a vertiginous leap into the unknown, at the frontier between suicide (his favourite visual representation) and going back to square one. Apparently, it was either that or nothing, after he had thrown in the towel on Mindhunter, on the verge of a burn-out. "I couldn't take it anymore, I needed a break, and that's why I suggested Mank to them,” he said. I imagine that they regret it already, because it's still a funny thing to make a movie about another movie. A film that even requires the spectator to have some understanding of this other film to know where they’re going. Is it worth it? I believe so. Are people likely to allow you to do this? Seems so. Sometimes…”

Throughout the following interview, Fincher comes back to his own way of doing cinema, often laborious, frustrating, his love of collaboration (with writers, his teams, “getting his hands dirty”) and his hatred of compromise (with reality, studios, “the little procedural pettiness” on-shoot). The parallel with the Citizen Kane adventure is striking, where a 24-year-old guy got carte blanche from the studios, which he transferred to his screenwriter (Herman J. Mankiewicz), to write while protected from any external pressure. Eighty years later, in a completely different context, Mank is also a film that invented extraordinary circumstances for itself, resembling nothing that has been done so far. That means, to no other film nor for any expediency.

In the course of general considerations on Herman Mankiewicz, David Fincher has undoubtedly given us one of the keys to his processes. “We always imagine that it’s enough to give a bundle of money to the best and that they will put as much effort and talent to the service of a third-rate order as they do for personal projects that fascinate them ... But it does not work like that. No chance.” More so than for Mank, you would swear he’s speaking about “Finch”. The only real subject of our interview.

PREMIERE: Between Madonna's Oh Father music video and the “fortresses of solitude” that you find in almost all of your films, it seems like you are deeply connected to Citizen Kane.

DAVID FINCHER: Yeah, it goes back a long way. The genesis of this film actually dates from the retirement of my father [Jack Fincher]. He had had a good career as a journalist [he was editor-in-chief of Life Magazine]. In the 60s, 70s, he had tried scriptwriting, but it didn't work out. There, all of a sudden, he found himself with a lot of time, not much to do to take care of himself, and he asked me if there were any subjects he could test himself on.

That was when?

1990, 1991, something like that. Right after filming Alien 3, I’d say… And I thought back to Pauline Kael's essay, Raising Kane, which we had discussed so much when I was younger. You should know that my father was crazy about cinema. As a child, I was always curious to know who he considered to be the best actor, the best director, the best sound engineer or the best director of photography. And for him, the best American movie ever made was Citizen Kane, without any doubt. When I was 9 or 10, I had no idea what “Citizen Kane” meant! I just knew it was about a journalist, like all his favourite films throughout his life - His Girl Friday, All the President's Men, The Front Page… But there you are, in 1970, 1971, seeing a thirty-year-old film meant it had to be shown on TV or in a studio cinema. The opportunity finally presented itself to the college. I must have been in 7th grade, there was a grade school trip to see a 16mm copy of Citizen Kane. My father was very excited. At that age, I had already seen Spartacus, 2001, Lolita, and Dr Strangelove. For me, the "old movies" were that, stuff from 1962 [the year he was born]. So, a film shot more than thirty years before, it was like hieroglyphics or murals in caves. I had no idea what I was going to experience.

And?

It was a real epiphany, a devastating shock. I felt both the film’s modernity and its classicism, its intensity and conciseness. And then there were these lines… “If I hadn't been so rich, I could have become a great man." Even at 12, you say to yourself, "Wow, this is good!”.

Your father must have been happy.

When I got home, we talked about it at length. He explained to me the very nature of classicism, why the themes remained contemporary, why it had gripped me so much when it had in theory not been made for a 70’s pre-teen northern Californian. In short, this film served as a bridge to talk more deeply about cinema. A while later, I read Pauline Kael's book on microfiche in the library. Until then, I had never heard of Herman Mankiewicz, nor imagined that the work of a screenwriter could have such an impact on the style of a film. I was simply not aware of the fact that writing and directing were two separate disciplines but equal - and also decisive - in the success of a cinematographic work. Subsequently, at 18-19, I came across it in my father's office, where there was the sofa I was sleeping on, during a weekend at my parents' house. So, when he retired and was looking for a “topic”, that was the first suggestion I made to him.

And he started to write it.

Yes. Later, he made me read his first draft. And, how can I say it, it was… like reading a leaflet from the Writer's Guild of America - a film made to denounce the injustices suffered by screenwriters, eternally mistreated by directors, who did not hesitate to play on their position to take ownership of their work. Hmm, OK… Me, I was just coming back from Alien 3 and I had had the exact opposite experience - a bunch of mercenary writers, one after the other, without anyone taking things seriously enough to try to make the film coherent. There you have it - it was just a movie about an egomaniac wiping his shoes on a poor screenwriter. Too simplistic for me…

Did he take your comments the wrong way?

No, he was aware of not having invented nuclear fission.

So it was you who brought about the changes, especially all the political background, concerning the story of the activist writer Upton Sinclair and the Californian elections for Governor in 1934?

No. Two years after his first draft, Jack came across a documentary that spoke about how Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg had got involved in this campaign, by putting the studio's resources to the service of their political opinions. Imagine the shock for such a film-enthusiast, who until then revered MGM, the studio Rolls-Royce. He was fascinated by the story of Sinclair, his EPIC [End Poverty in California] movement and how MGM, in order to discredit him, sort of invented fake news. By grafting that onto the story of the creation of Citizen Kane, he came up with a new draft that went a bit all over the place, but opened up an interesting perspective on what might have played out in the relationship between William Randolph Hearst, one of the most powerful men, and Mankiewicz, one of the most brilliant minds of the time. A guy that Ben Hecht and all the guys from Hollywood's Algonquin Round Table [an influential group of writers and co-opted socialite screenwriters] agreed to put on a pedestal. Frankly, if Ben Hecht thinks you are a genius, you have to be one, right? I was not quite sure how to translate this from a dramatic point of view yet, but I liked the idea of this man whose only contribution to the writing of The Wizard of Oz, for which he had been hired, had been to say, "Kansas in black and white, Munchkinland in colour," one of the most unforgettable film effects of all time. A kind of casual hitman, who lands on a project in difficulty, throws in a brilliant idea and then goes quietly for a drink, convinced that he is much better than that anyway. There, we held a real angle for the character.

But the project did not come off.

We made lots of corrections, we threw things back and forth, I cut out all his adverbs, he put a good third of them back in… And then, around 1997, 1998, just after The Game, we almost did it with Polygram - a big independent arthouse film. But they withdrew at the last moment, saying, ‘Who is this film for?’ Well, we can't blame them totally either, eh ... There you go, it stopped dead in its tracks. We put all this work on a shelf, where it had been collecting dust ever since. Jack died in 2003 after two years of battling pancreatic cancer. I had resigned myself, I said to myself, well maybe my daughter will read it one day… And then at the end of season 2 of Mindhunter, I was completely done for. I went to see Ted Sarandos and Cindy Holland [the directors of Netflix programs] to say, “Look, I don't see myself going back for two years on a third season, I'd rather spend a year on a more modest project, have the luxury of spending six months of pre-production designing two hours of content rather than ten…” They said, “OK, what've you got?" I passed over the Mank script, without much hope. But they were up for it. I replied, "When do we start?”

We’re used to considering Welles like a kind of Superman, the “one-man-band” of cinema, a genius, a force of nature who…

(He cuts in.) Really? No, not anymore. With time, we realized that he was above all a showman and a showman with disproportionate talent who had his chance but who… Finally, excuse me, I cut you off…

Yes, but now I want to know what you were going to say ...

Well ... I think the tragedy of Orson Welles lies in the mixture of monumental talent and grimy immaturity. Of course, there is genius in Citizen Kane, who could dispute that? But when Welles says, "It only takes one afternoon to learn everything you need to know about photo direction,” well… You’d say the comment comes from someone lucky enough to have Gregg Toland a yard away from him preparing the next shot… Gregg Toland, damn it, an unbelievable genius! I say this without wanting to be disrespectful to Welles, I know what I owe him, as I know what I owe Alfred Hitchcock, Ridley Scott, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas or Hal Ashby. But at 25, you don't know what you don't know. Period. Neither Welles nor anyone. It doesn't take anything away from him, and especially not his place in the pantheon of those who have influenced entire generations of filmmakers. But claiming that Orson Welles came straight out of the blue to make Citizen Kane and that the rest of his films was spoiled by interventions of people with the wrong intentions is not serious, and is to under-estimate the disastrous impact of his own fits of delusional hubris. I can't say anything about The Magnificent Ambersons, because I never saw the Welles version, before it was re-edited…

None of us saw it.

No. But we have seen The Trial, we have seen The Stranger ... even Touch of Evil. And all of them would have benefited from being shot by Gregg Toland and written by Herman Mankiewicz, don't you think?

So you clearly side with Pauline Kael, who saw Mankiewicz's script as the real key to the film's success.

It is more complicated than that. First of all, because it's all well and good having a good script, you still have to interpret it in images, the scenography, to bring it to life in three dimensions on the set. And that is the director's job. Secondly, because the rest of Mankiewicz's filmography didn’t let us predict such a thing ... Frankly, who was expecting Citizen Kane from the guy who had overseen Duck Soup?

Duck Soup is very good!

(Laughs.) You have to understand that Mankiewicz had an erratic, angry personality, probably not suited to the studio system, which had partly broken him. And there, Welles gave him access to the fast lane - total carte blanche, and no accountability to the guys in the studios whose preoccupation was to convince the Americans of the Great Depression and to drop their 25 cents to see a movie. Plus, he was working in the shadows, incognito, on behalf of someone who encouraged him to put everything he believed in into his script and throw his punches. The real reason for its success is there. And the tragedy is that this is also the reason for the quarrels which followed between the two men - Mankiewicz had accepted the deal, agreed to work on behalf of these arrogant New Yorkers who wanted to show it off to the people of Hollywood, and he would never have written it all if he had thought he'd be credited in the titles. But when he realized that this would be his biggest contribution to cinema, he changed his mind.

A good idea in terms in terms of posterity, less so for his career at the time.

Yes, because you shouldn't wake up a sleeping bear, in this case Hearst, who fixed himself on the film and all those who had participated in it ... But in short, I wanted to make a film about the true nature of the collaboration. On the one hand, this is the very first example of such nuanced, rich, deep writing, applied to mythologizing a man and dissecting his life, live. On the other, there’s Toland, one of the men who best understood how to use a camera to tell a story. And in the middle, this 24- 25-year-old Mr. Loyal who did not accept being told no and stubbornly refused to listen to those who wanted to explain to him what cinema could or should be, and what was technically feasible or not. Having that self-confidence at that age, damn it, it's phenomenal. At the end, I wouldn't say it's the best American movie ever made. Personally, I prefer to watch All The President's Men, Chinatown or Being There. But thanks to those three things put together, it's at least one of the top ten or fifteen. And in many ways the first.

You have a very balanced line for a director who is never the author of his own scripts.

I am the son of a man who wrote for a living. I know what it is. All my childhood I saw him tapping his big fingers on his 1928 Underwood and cutting ten or twelve pages a day in extreme solitude to pay the bills. And believe me, it's not my idea of fun… Even if I hate filming and its petty procedural pettiness, where you have to make “artistic” decisions in four minutes because there’s a lunch break and you're going to get yourself a penalty, I know for a fact that it's nothing compared to being stuck at your desk all day trying to pull something out of the bag that holds up.

Are you aware of your status with critics and true cinema obsessives today? People who continue for the most part to subscribe to the theory of authors, for whom directing remains cinema’s cardinal value?

Never forget that this theory was developed by critics who dreamed of becoming directors! Incidentally, I love reading Pauline Kael, I esteem her contribution to American cinema, but we could fill several volumes with what she did not know about the way films are made. And so much the better, because the critics are not supposed to know, if only because it would greatly damage the mystery that surrounds this craft.

But you are making a film that deliberately goes against this mystique.

Cinema is an incredibly human enterprise, in all that the word signifies in terms of fragility, disorganization and pathos. We have always tried to militarize this artistic activity but, no offense to the studios of yesterday and today, these are two concepts that cannot co-exist. This is the original error in everything that has to do with cinema - you can approach it as a paramilitary operation, you can organize it like an assembly line, but that will never prevent the person at the controls, the one who has the responsibility for choosing the angles and recording the material, of being the plaything of circumstances that escape any planning. I can tell you - no one has their entire film in their heads. No one. Or, this is a damn light film… Imagine that we can say, “This is what I want” and then the dominoes will fall exactly as planned, that is hogwash. You know, I’ve had days of meetings with twenty-six heads of post around a table, where we take the script page by page, "OK, so, there, this scene, it's supposed to express this, we will need that, the girl will have to have her hair in a mess, we will need to plan for several blouses because of the sweat… ” and of course, these things then need managing. But we have to put it into perspective. We are not NASA, as far as I know, and although I am quite strong and very prepared, I would be unable to detail my intentions for each little moment of the film.

From the outside, one gets the feeling that there is only one person who does not sleep during the making of a film because he’s risking his life every time - the director.

In my job, I have always considered it important that everyone sees me as the man who is there before everyone else in the morning and who leaves last in the evening, the chap capable of answering any question from anyone. I have said it before - I understand why Francis Coppola would have dreamed of being able to direct from his caravan. Yes, I understand that. Because arriving on set, with all these eyes on you, these open-mouthed people waiting for your instructions in "What now, Captain?" mode, it is not a very enviable position, it cannot help you to feel good about yourself. You invariably come out of it saying to yourself, "Hey shit, shouldn't I have thought twice before making that decision?" Did I hurt someone again?” Yes, I understand wanting to escape from that, the weight of 3000 - what am I saying - 35000 questions a day that you have to be ready to answer. I understand that we prefer giving instructions into a microphone, then going away and relaxing while reading a book or surfing the Net while the team is working, before springing back in like a primrose to check on the monitor that everything is in order…

But it doesn't work that way…

I'm sorry, but no. You have to roll up your sleeves and dip your hands in the sludge, in the sweat, in the dirt, your hair smelling of grease, like everyone else. Because it is there, in the field, that we can shape the will of the team members and get hold of the good ideas. You can't imagine the number of times a photo director or even a set photographer has told me, "Why not put a second camera in that corner, that would save a set ..." and that I then realize that the scene is a thousand times better from this angle. So, authorism, sorry, I don't believe it. And, I hope that Mank speaks about this, in its own way. About the relationship between these different creative forces that must be successfully brought together. Knowing that even when the result is good, you cannot avoid resentment and annoyance, just because there is not always a polite way of saying to someone, "I don't believe in this idea and I don't have the time to try it." Ah, speaking to you, I can see how ironic it is that a film on such a subject has been conceived out of spiteful e-mails between a father and his son, where one said, "You really don't understand anything about older men…” and the other, “We can see that you do not know the difference between a studio executive and a producer”. Still, yeah, we can say that it was a funny collaboration.

Mindhunter may have something to do with it, but the more we go on, the more it seems that you are fascinated mostly by the psychological aspect of the characters. Fincher, psychological film-maker, is that a ridiculous thing to say?

In fact, it's rather fun to hear. I am always interested in characters acting as much on what they want as in spite of what they want. For me, this is the difference between text and subtext. On the one hand, there is what the character says; on the other, what's really going on inside him ... The two aspects can be simultaneously Siamese and opposite, go hand in hand or conflict with each other. People act incredibly self-destructively, and sometimes they are even fully aware of doing it. It is a fascinating thing in human beings, therefore a fascinating thing in the characters of a film.

Stylistically speaking, with the jazz soundtrack, in black and white, and with two men who confront each other from a distance, I thought of Alexander Mackendrick's Sweet Smell of Success, which I am told is one of your favourite films.

A crazy movie. You know, directors look at films in a pretty special way. We all have a kind of lexicon. For us, plans are common nouns, verbs, together they form sentences or paragraphs, a language, and this language is constantly evolving. An example, which has nothing to do with it - I can see a shot of a man blowing out a match and another of a sunrise and explain to you why this connection cannot work, because we see that the matchstick guy is filmed in the studio, where the light is too blue on a face that is way too made up and that in 70mm it's going to be awful. Above all, do not do that, fellas! But David Lean does it [in Lawrence of Arabia], and it becomes one of the greatest movie ideas ever. Sometimes the power of an idea is such that it overcomes everything, even technical imperfections. A connection between a bone and a spaceship; “Kansas in black and white, Munchkinland in colour…” You see? All that to say that there are references posted in Mank - The Grapes of Wrath, How Green Was My Valley, but that Sweet Smell of Success is part of my lexicon, it is there even when I don't consciously refer to it. I love it because it stays true to its concept all the time. It never stops to take you by the hand, it pulls you in, period. For Mank, we had a decisive choice to make - should we explain who Irving Thalberg is or who Louis B. Mayer is, beyond the rugged businessman whose name is in gold letters on his door? No, otherwise the film would last an hour longer. So yes, your analogy is fair - these are two films that demand a lot from the viewer. Prerequisite knowledge and a lot of attention during the screening.

Did the fact that it was your father’s script have any bearing on your way of appropriating the project? Some gimmicks, including typewritten time cards, suggest that you approached the text with more reverence than usual.

I feel that I have always treated my writers with a lot of respect. But I reserve the right to question their choices when they present their work to me, father or not. I imagine it was not easy for Jack to hear his son’s remarks, who had only done Alien 3, a few clips and Pepsi ads… If we could have shown him the finished film, I wouldn't have been surprised if he had told me: “Well, poor chap, you're way off the mark. Yet it was clear.” Even some elegant and well-crafted little solutions that we are very happy with would have gone down badly with him. But it's true, there were also a few occasions during the shoot where I stuck to what was on paper, whereas in normal times I would have questioned the screenwriter. But, unfortunately, he was not available… So, there you have it, I'm not going to lie to you - I don't recommend other directors to make films written by their father! Essentially, I have always considered that I was firstly responsible to my writers. But I know them too well to imagine that they may be happy in the end. Afterwards, none of those I have worked with will tell you that I was cruel to them.

No, of course, that was not the point of the question.

We sometimes have to say to them on TV, “Okay, guys, we're shooting tomorrow morning, so you have between dinner and one in the morning to find the best possible solution.” Not in cinema. On the other hand, I’ve been known to say: "No, I cannot shoot that, because I do not believe in it ..." And that also happened on this film, even in the absence of my father.

Do you dream that he could win a posthumous Oscar?

Oh no, no, frankly, I don't like to think that way at all. I think the real exorcism was to take the project out of the drawer and make it exist. That's all I needed. The rest ...

Are you 100% connected to Netflix now?

Yes, I have an exclusive contract with them for another four years. And depending on the way Mank is received, I'm either going to go sheepishly and ask them what I can do to redeem myself, or present myself as an arrogant asshole demanding to make more films in black and white. (Laughs.) No, I'm here to deliver "content" to them - whatever that word means - that might get them spectators, in my little sphere of influence.

Gone Girl dates from 2014, it was dragging on, right?

I did both seasons of Mindhunter and… Initially I just had to help get the show back on track, I wasn't meant to be a showrunner. And then, by default, I became it, along with two other people. And let's say that it is possible that this is not my strong point, after all. I must be too obsessive and finicky to take on this role.

In the end, there are still very few films signed David Fincher ...

What do you want, I'm slow. When I have the feeling that something is ready to be shot, it can go really fast. The Social Network, everything was in place, we just had to choose the actors. But those situations are rare, cases where you read a script and say, “OK, guys, step aside, let's get going.” Around 2007-2008, then 2010-2011, I did it relatively quickly, at least according to my usual standards - Zodiac and Benjamin Button then The Social Network and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. But I'm not sure it was such a good thing in the end. Anyway, I needed to recharge my batteries. Now, if I signed this Netflix deal, it's also because I wanted to work in the way Picasso painted, to try very different things, to try to break the form or to change the way of working. I like the idea of having a "work". Yes, I admit that it makes me weird, after forty years in this business, to have only ten films to my credit. Well, eleven, but ten that I can say are mine. Yes, objectively, it is a rather terrifying observation.

Commentaires